Air Conditioner Troubleshooting

How to save a few hundred dollars, maybe

Air Conditioning is nearly universal where I live in the southeastern United States, usually as part of a “central HVAC” installation. I know very little about Air Conditioners; I studied the thermodynamic cycles in college, but most of what I know has come from troubleshooting my own A/C when something has broken. Sometimes this has just helped me to keep the house cool while I wait for a service call - but most of the time, I’ve been able to fix the problem entirely, and I’ve probably saved enough by now to cover the cost of a new Air Conditioner.

When I started writing this, I hoped to give you enough context to do some of this basic troubleshooting on your own and to decide whether to attempt a repair yourself. But this is a big, complicated problem space, well outside my area of expertise, and it’s been hard to condense - so instead, I’m going to focus on a couple examples of HVAC failures I’ve been able to fix myself.

How Air Conditioners Work

An air conditioner is a pump that moves heat from the inside of your house to the outside. I find it helpful to imagine a machine that brings dry sponges into my home to soak up heat and then transports them outside to wring them “cool” again. Some air conditioners can be run in reverse as a heat pump to heat a home in winter.

A central air conditioner is actually two separate but interdependent machines. The inside machine has a big fan and a heat exchanger; this device doesn’t particularly care whether you’re heating or cooling or whether your cooling comes from air conditioning or cold water or magic. The outside machine has a big fan and a compressor.

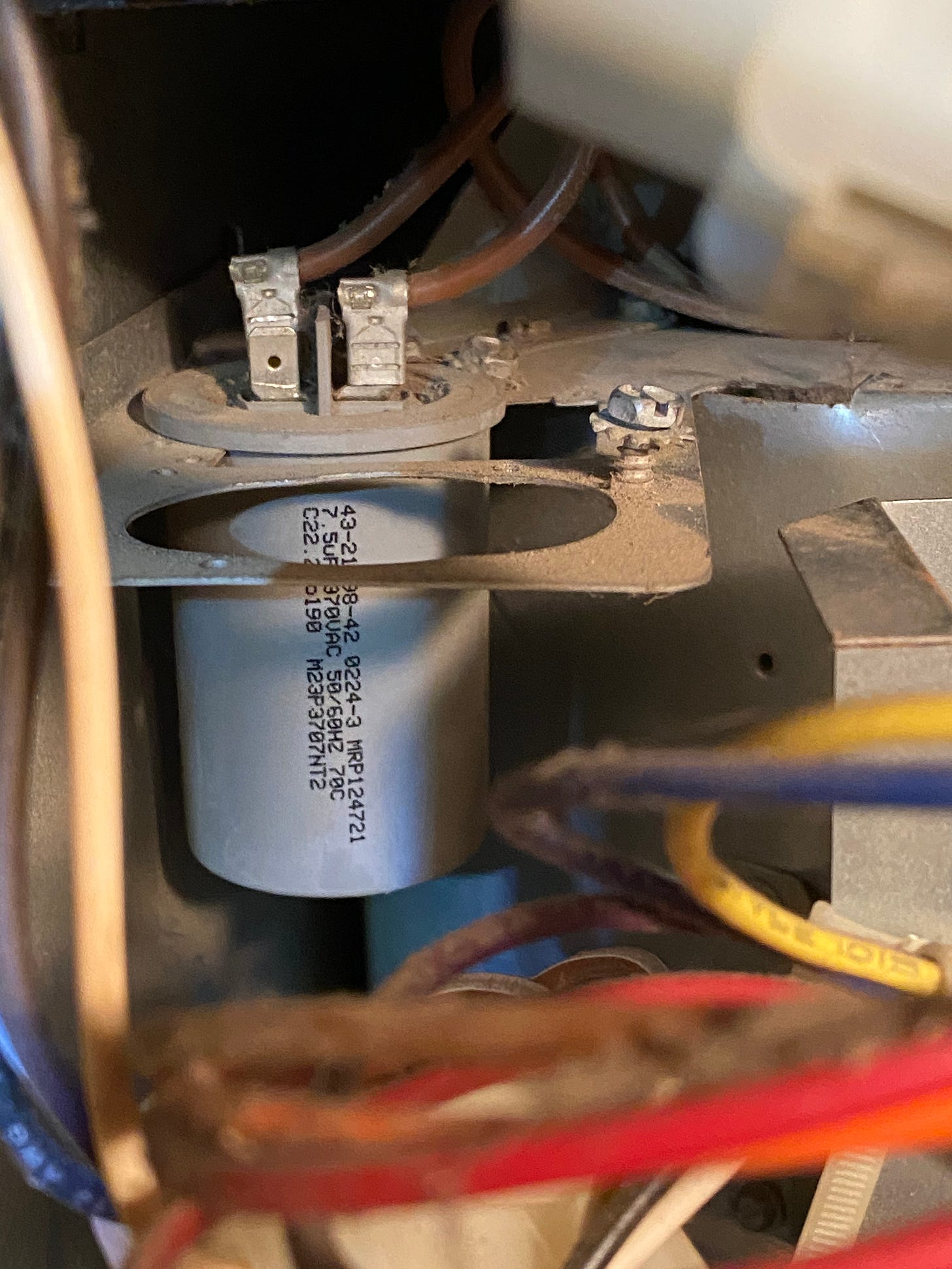

Capacitors

It takes a great deal of electrical current to start a furnace fan or A/C compressor - much more than it takes to keep it running - so the fans and compressors each have their own “start capacitors” (and may also have their own “run capacitors”). These capacitors seem to fail a lot (I think I’ve replaced five of them in the past fifteen years), but the good news is that they’re so cheap and easy to replace that I now just preemptively replace my capacitors before scheduling a service call - and most of the time, that fixes the issue. I get my replacement caps at Grainger - they have several locations near my home, so I can usually get a replacement part the same day as I realize I need it

I’m not to go into detail about how to do a capacitor replacement - there are many good Youtube videos that cover this - but I do want to reiterate that if you do this, make sure:

Your equipment is powered off and the old capacitor is discharged

You’re wearing appropriate safety gear

You’ve bought a replacement capacitor with the same specifications as the one you’re replacing. The type, voltage ratings, and capacitance are all Very Important.

Make sure you pay attention to which wires were connected where!

General Troubleshooting

Even if the problem turns out to be a capacitor, it helps to be able to narrow down which capacitor needs to be replaced - your system may have three or more - and whether there are other problems as well. Here are some questions to consider:

Make sure you don’t have a tripped circuit breaker in your electrical panel; also check whether the high-pressure switch tripped (it’s usually a little red button that looks like a turkey timer mounted on the outside unit).

Can you identify one part of the system that isn’t running? For example, you don’t feel air blowing inside, or you don’t see the fan spinning in the unit outside. These offer a good clue of where you may want to focus your attention.

Does the behavior change over time? For example, if you feel cold air when your system first starts running, but the airflow decreases over time, it’s probably not a capacitor. (I ran into this on a couple occasions when the coolant line was under-pressurized - the heat exchanger would ice up and block the airflow. In both cases I ended up needing to replace the entire unit.)

Does the entire system lose power entirely, where the thermostat says something like “No power, system offline”? This happened to me earlier this summer and I eventually figured out it was due to a clogged condensate line; as the water backed up into the evaporator, it triggered a safety switch that cut off power to the entire unit.

Miscellanea

To unclog my condensate line I had to cut off a section of PVC pipe. When I replaced it, I added a removable cap so that I can more easily service the line in the future. I also added a reminder to my spring maintenance checklist to clean the line.

I installed 5-2-1 Compressor Saver Capacitors on my outside units. I don’t know how much they’ll actually help, but I was told in 2017 that our downstairs air conditioner was about to fail, and it hasn’t failed yet…

Our newest air conditioner came with a ten year warranty, as long as we signed up for an annual maintenance plan that would cost us ~$300/year. I decided that the unit was unlikely to fail within ten years, and that the $3000 I’d save on the contract over ten years would go a long way toward paying for a new unit. I kept a copy of the “service checklist” from my initial visit and have used it to do my own “annual maintenance” every fall; here’s a condensed version:

Change the air filter (one of my units has filters that need to be changed annually, while the other needs changing quarterly. I buy these from Costco and they cost 10-20% of what they do when I paid the HVAC installer to replace them.)

Check the air temperature from the unit

Check the pressure levels in the unit outside

Check the defrost cycle. (Pump keeps running with the fan off, brings some of the heat back outside, keeps ice from forming.)

Remove screws on the outside cage to access the controls, then test the voltage on the controls with my multimeter; reference values are printed on the outside of the case.

Test refrigerant levels. (I’ve never done this, and don’t have the equipment to do it, but it looks like the necessary tools are available on Amazon for ~$50)

Clean out leaves and debris

Clean the coils using condensate coil cleaner.

Straighten coil fins if needed using a fin comb

My downstairs HVAC has a condensate pump to pump condensate outside the house. When the drain line cracked apart a few years ago (I think the tube wasn’t rated for UV exposure), I replaced it with a longer line that connects to some drip irrigation emitters in my garden:

That’s it for this week - as usual, please leave a comment if you have questions or opinions about anything we wrote! Next week I’ll pick up again with the final episode of my Battery Trilogy.

A friend commented that this had "made it abundantly clear I don’t have the foggiest idea how my air conditioner works". So here's an attempt at a quick primer.

The inside portion of an air conditioner is philosophically the same as the inside of a furnace - you're blowing air across a heat exchanger that either adds heat or takes it away from the air that passes across it. It's easy to heat things - but how to make them cold? You could use blocks of ice, or a Peltier thermoelectric cooler, but air conditioners take advantage of the fact that gasses become cooler when they're expanded. The secret to air conditioning is to use a special "refrigerant" that can, through expansion, become much cooler than the ambient air - and then, through compression, become much warmer than the ambient air. You can then blow a fan over the expanded gasses to pull heat out of the air in your home - and then blow a different fan outside your home over the compressed refrigerant to pull the heat back out.

Imagine that your air conditioner is the "sponge machine" I mentioned above, and that the sponges soak up heat instead of water. You bring a dry sponge into your house, you allow it to soak water from the air that passes over it, and then you take it outside. When you compress it, it can't hold as much water, so when you blow a fan over it it dries out quickly. You then allow it to expand again and return it to the inside of your house.

One more side-note: there's a pretty compelling theory that Air Conditioning was a key factor in the mid-20th century political shift within the US as more people left northern cities to live in southern states. See, for example, https://www.washingtonpost.com/made-by-history/2022/08/08/air-conditioning-remade-politics-now-its-key-navigating-climate-change/ and https://chicago.suntimes.com/politics/2014/8/20/18572909/how-air-conditioning-remade-america